President Vladimir Putin declared two regions in the Donbas region independent, then ordered in troops.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has ordered troops into two Ukrainian regions held by Russian-backed separatists, a dramatic escalation that threatens to spiral out into a larger conflict.

Putin had amassed some 190,000 troops near the Ukrainian border and appeared to be making preparations for war. His decision Monday violates principles of international law, but isn’t yet being treated by the West as an invasion that the US promised would trigger a “massive” package of sanctions.

The question now is whether this is a preface to a much larger invasion of Ukraine.

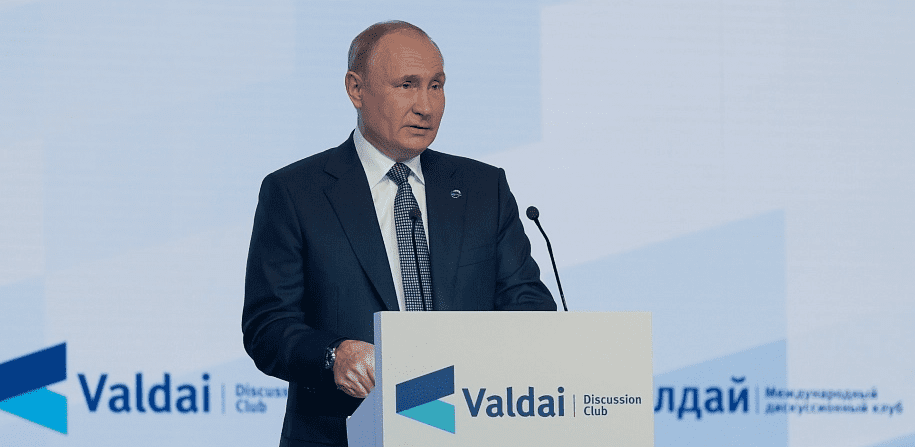

Though Russia hasn’t yet staged the large-scale land invasion that the Biden administration has been publicly warning about for several days, a dizzying series of developments over the weekend showed how the window for a diplomatic outcome has narrowed. After days of fabricated claims of Ukrainian aggression, on Monday Putin delivered a combative, hour-long speech on Ukraine, which essentially denied Ukrainian statehood and portrayed NATO as a direct threat to Russia.

In his speech, Putin recognized as independent the so-called Luhansk People’s Republic and the Donetsk People’s Republic, two territories in eastern Ukraine where he has backed separatists since 2014. “Otherwise, all responsibility for the possible continuation of the bloodshed will be entirely on the conscience of the regime ruling on the territory of Ukraine,” Putin said. “Announcing the decisions taken today, I am confident in the support of the citizens of Russia. Of all the patriotic forces of the country.”

Soon after, Putin announced the deployment of troops for “peacekeeping operations.”

Most experts Vox spoke to said this looks like the beginning, not the end, of Russia’s incursion into Ukraine, although it is impossible to predict events with certainty. Russia’s declaration of independence for the breakaway territories, and the move of peacekeeping forces into that territory, “sets the stage for the next steps,” said Michael Kofman, research director in the Russia studies program at CNA, a research organization in Arlington, Virginia.

“In Russia, [it] provides the political-legal basis for the formal introduction of Russian forces, which they’ve already decided to do,” he said. “Secondarily, it provides the legal local basis for Russian use force in defense of these independent Republic’s Russians citizens there. It’s basically political theater.”

What Russia does from here on out is likely to determine how the United States and its NATO allies respond to Russia’s actions. The White House has promised severe sanctions for a Russian invasion, but so far the US and European allies have just sanctioned the two breakaway regions.

Russia has tens of thousands troops along different parts of the border with Ukraine. It is a force capable, and in position, for a much larger scale operation. “Russia did not need to amass 190,000 troops in order to just recognize the independence of Donetsk and Luhansk,” said Natia Seskuria, an associate fellow at the Royal United Services Institute.

Is this the invasion the world has been watching for?

In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea and invaded eastern Ukraine, backing pro-Kremlin separatists in the regions of Luhansk and Donetsk in a conflict that has simmered for years and killed at least 14,000.

Shelling from the Russian-backed separatist side of the border intensified in recent days, with separatist leaders blaming — without evidence — Kyiv for the fighting, and calling on its residents to evacuate. By Monday, Putin had called a meeting with his security council to discuss the situation, then hours later declared these breakaway regions independent, sending in forces for what he described as a “peacekeeping” mission.

Olga Lautman, a senior fellow at the Center for European Policy Analysis, described this as an invasion. But she also said that it was likely a distraction — laying a foundation for more steps to come. Rep. Liz Cheney tweeted, “Russia has invaded Ukraine,” and Michael McFaul, who served as Obama’s ambassador to Russia, said the same.

Kofman, of CNA, described it as a “renewed invasion,” building on what happened in 2014 and 2015. Analyst Anatol Lieven of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft wrote, “This would fall far short of invasion. It would mark only a limited escalation in the conflict that has been going on in the Donbas since 2014.”

It’s unclear if this escalation will lead to Russian troops directly engaging Ukrainian ones, or what will happen on the ground in these declared independent regions in the coming days.

But this distinction of what is and isn’t an invasion matters, as it will direct how the United States and its allies will respond. On Monday evening, the White House issued an executive order with sanctions against those doing business in the breakaway republics. But the US has yet to call recent developments an “invasion,” and in summaries of President Joe Biden’s calls with European leaders, the White House described the events as an “ongoing escalation along the borders of Ukraine” and a “clear attack on Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

A White House official told reporters that while the administration did not yet rule out more severe sanctions, it will “assess what Russia does and not focus on what Russia says.”

How did it come to this?

The world has been closely watching Russia’s troop movements on the Ukrainian front since November. Late last year, Moscow issued the United States a series of demands. They included some big asks, including a guarantee against Ukraine’s eventual NATO membership and a commitment for NATO to roll back some of its troop deployment in countries recently admitted to the alliance. These were non-starters for the US and its allies, as they would effectively give Russia veto power over the alliance’s decisions — and over European security.

Still, diplomatic efforts followed, with the US and Russia negotiating for most of January, and European and US leaders cycling through Ukraine and Moscow. Even as these efforts took place, Russia’s mass mobilization of soldiers around Ukraine in recent weeks has signaled Putin’s interest in maintaining the option of a full-fledged land war in Europe.

The reasons for this conflict are complex, rooted in post–Cold War history and Russia’s 2014 invasion of Ukraine, and raise larger questions about the place of the US and Russia in the 21st century.

NATO’s eastward expansion to former Soviet republics on the Russian border since the Cold War ended hasn’t helped. Biden’s CIA director, William Burns, who served as ambassador to Russia from 2005 to 2008, had predicted that giving Ukraine NATO membership would “create fertile soil for Russian meddling in Crimea and eastern Ukraine.” (Ukraine isn’t part of NATO and was not expected to join anytime soon, but the country has deepened cooperation with the West since 2014).

But Putin has dismissed Ukrainian sovereignty entirely. In Monday’s speech and in a July 2021 essay, he claimed Ukraine is part of a “unified state” with Russia. The decision to move troops in doesn’t mean Russia is officially annexing Donetsk and Luhansk — yet — but it does escalate efforts to pull the country back into Moscow’s orbit.

Previously, Russia’s plan had been to pressure Ukraine to adopt the 2015 Minsk Agreement that would allow Ukraine to regain formal control over the Donbas rebel-held areas in return for granting their proxies an outsize role over decision-making in the capital of Kyiv, said Samuel Charap, a senior political scientist at the RAND Corporation.

Putin’s actions on Monday signaled a new direction. “Today, [Russia] declared the Minsk agreements dead completely, which means that the era of Russia trying to achieve its objectives through a negotiated return of the Donbas is over,” Charap said. “It means they’re about to get to establish their influence through the use of force.”

What happens next?

Putin is likely one of the only people who knows what comes next. But the diplomatic pathways out of this conflict are rapidly closing, and experts say that Putin looks to be building a pretext he may need to carry out a more robust attack on Ukraine — possibly going so far as threatening the capital of Kyiv. This is the worst-case scenario that the White House has warned about: a war that will cost tens of thousands of lives and potentially spur a mass refugee crisis.

Putin’s escalation in eastern Ukraine occurred the day after French President Emmanuel Macron spoke with the Russian leader for hours, which seemed to point to a possible diplomatic out — specifically, an agreement “in principle” for a summit between Presidents Biden and Putin, after Secretary of State Antony Blinken and Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov were scheduled to meet Thursday. Russia’s latest actions almost certainly have jeopardized any sort of high-level summit, said Rajan Menon, director of the Grand Strategy program at Defense Priorities.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky said in an address Monday that Putin’s incursion was a violation of the country’s “national integrity and sovereignty.”

“We are on our land, we are not afraid of anything and anyone, we don’t owe anything to anyone, and we will not give away anything to anyone. And we are confident of this,” Zelensky said.

Ukraine, though, doesn’t have many options. The Ukrainian army, if it returns fire, risks giving Russia the exact pretext it would need to attack. And experts noted that Russia is already trying hard to manufacture the evidence for that pretext, with or without Ukrainian involvement.

That all feeds into Putin’s recent moves, and what he might do next. Putin’s formal recognition of the independence of the two breakaway regions in eastern Ukraine created a justification for a formal military presence in the area. Moscow has been circulating fake videos on Russian state media of alleged Ukrainian attacks. Even if some of these videos are poorly produced, US intelligence officials and experts have repeatedly suggested Russia might attempt to manufacture a “false flag” attack as a provocation to justify more robust military force.

“By recognizing the independence of Russian-occupied Ukrainian territories, Donetsk and Luhansk, the Kremlin has laid the foundations for its ambition to achieve main goals of the regime change and erasing the Ukrainian sovereignty, hence the return of Ukraine into Russia’s sphere of influence,” Seskuria, of RUSI, said.

That hasn’t happened yet. But the question is what — if anything — could move Putin from a course toward a takeover.

As Biden himself noted in 2018 while speaking about Russia at the Council on Foreign Relations, “My dad had an expression, ‘Never back a man in a corner whose only way out is over top of you.’ Well, you know, take a look at Russia now. Where do they go?”

READ President’s address

Citizens of Russia, friends,

My address concerns the events in Ukraine and why this is so important for us, for Russia. Of course, my message is also addressed to our compatriots in Ukraine.

The matter is very serious and needs to be discussed in depth.

The situation in Donbass has reached a critical, acute stage. I am speaking to you directly today not only to explain what is happening but also to inform you of the decisions being made as well as potential further steps.

I would like to emphasise again that Ukraine is not just a neighbouring country for us. It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture and spiritual space. These are our comrades, those dearest to us – not only colleagues, friends and people who once served together, but also relatives, people bound by blood, by family ties.

Since time immemorial, the people living in the south-west of what has historically been Russian land have called themselves Russians and Orthodox Christians. This was the case before the 17th century, when a portion of this territory rejoined the Russian state, and after.

It seems to us that, generally speaking, we all know these facts, that this is common knowledge. Still, it is necessary to say at least a few words about the history of this issue in order to understand what is happening today, to explain the motives behind Russia’s actions and what we aim to achieve.

So, I will start with the fact that modern Ukraine was entirely created by Russia or, to be more precise, by Bolshevik, Communist Russia. This process started practically right after the 1917 revolution, and Lenin and his associates did it in a way that was extremely harsh on Russia – by separating, severing what is historically Russian land. Nobody asked the millions of people living there what they thought.

Then, both before and after the Great Patriotic War, Stalin incorporated in the USSR and transferred to Ukraine some lands that previously belonged to Poland, Romania and Hungary. In the process, he gave Poland part of what was traditionally German land as compensation, and in 1954, Khrushchev took Crimea away from Russia for some reason and also gave it to Ukraine. In effect, this is how the territory of modern Ukraine was formed.

But now I would like to focus attention on the initial period of the USSR’s formation. I believe this is extremely important for us. I will have to approach it from a distance, so to speak.

I will remind you that after the 1917 October Revolution and the subsequent Civil War, the Bolsheviks set about creating a new statehood. They had rather serious disagreements among themselves on this point. In 1922, Stalin occupied the positions of both the General Secretary of the Russian Communist Party (Bolsheviks) and the People’s Commissar for Ethnic Affairs. He suggested building the country on the principles of autonomisation that is, giving the republics – the future administrative and territorial entities – broad powers upon joining a unified state.

Lenin criticised this plan and suggested making concessions to the nationalists, whom he called “independents” at that time. Lenin’s ideas of what amounted in essence to a confederative state arrangement and a slogan about the right of nations to self-determination, up to secession, were laid in the foundation of Soviet statehood. Initially they were confirmed in the Declaration on the Formation of the USSR in 1922, and later on, after Lenin’s death, were enshrined in the 1924 Soviet Constitution.

This immediately raises many questions. The first is really the main one: why was it necessary to appease the nationalists, to satisfy the ceaselessly growing nationalist ambitions on the outskirts of the former empire? What was the point of transferring to the newly, often arbitrarily formed administrative units – the union republics – vast territories that had nothing to do with them? Let me repeat that these territories were transferred along with the population of what was historically Russia.

Moreover, these administrative units were de facto given the status and form of national state entities. That raises another question: why was it necessary to make such generous gifts, beyond the wildest dreams of the most zealous nationalists and, on top of all that, give the republics the right to secede from the unified state without any conditions?

At first glance, this looks absolutely incomprehensible, even crazy. But only at first glance. There is an explanation. After the revolution, the Bolsheviks’ main goal was to stay in power at all costs, absolutely at all costs. They did everything for this purpose: accepted the humiliating Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, although the military and economic situation in Kaiser Germany and its allies was dramatic and the outcome of the First World War was a foregone conclusion, and satisfied any demands and wishes of the nationalists within the country.

When it comes to the historical destiny of Russia and its peoples, Lenin’s principles of state development were not just a mistake; they were worse than a mistake, as the saying goes. This became patently clear after the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

Of course, we cannot change past events, but we must at least admit them openly and honestly, without any reservations or politicking. Personally, I can add that no political factors, however impressive or profitable they may seem at any given moment, can or may be used as the fundamental principles of statehood.

I am not trying to put the blame on anyone. The situation in the country at that time, both before and after the Civil War, was extremely complicated; it was critical. The only thing I would like to say today is that this is exactly how it was. It is a historical fact. Actually, as I have already said, Soviet Ukraine is the result of the Bolsheviks’ policy and can be rightfully called “Vladimir Lenin’s Ukraine.” He was its creator and architect. This is fully and comprehensively corroborated by archival documents, including Lenin’s harsh instructions regarding Donbass, which was actually shoved into Ukraine. And today the “grateful progeny” has overturned monuments to Lenin in Ukraine. They call it decommunization.

You want decommunization? Very well, this suits us just fine. But why stop halfway? We are ready to show what real decommunizations would mean for Ukraine.

Going back to history, I would like to repeat that the Soviet Union was established in the place of the former Russian Empire in 1922. But practice showed immediately that it was impossible to preserve or govern such a vast and complex territory on the amorphous principles that amounted to confederation. They were far removed from reality and the historical tradition.

It is logical that the Red Terror and a rapid slide into Stalin’s dictatorship, the domination of the communist ideology and the Communist Party’s monopoly on power, nationalisation and the planned economy – all this transformed the formally declared but ineffective principles of government into a mere declaration. In reality, the union republics did not have any sovereign rights, none at all. The practical result was the creation of a tightly centralised and absolutely unitary state.

In fact, what Stalin fully implemented was not Lenin’s but his own principles of government. But he did not make the relevant amendments to the cornerstone documents, to the Constitution, and he did not formally revise Lenin’s principles underlying the Soviet Union. From the look of it, there seemed to be no need for that, because everything seemed to be working well in conditions of the totalitarian regime, and outwardly it looked wonderful, attractive and even super-democratic.

And yet, it is a great pity that the fundamental and formally legal foundations of our state were not promptly cleansed of the odious and utopian fantasies inspired by the revolution, which are absolutely destructive for any normal state. As it often happened in our country before, nobody gave any thought to the future.

It seems that the Communist Party leaders were convinced that they had created a solid system of government and that their policies had settled the ethnic issue for good. But falsification, misconception, and tampering with public opinion have a high cost. The virus of nationalist ambitions is still with us, and the mine laid at the initial stage to destroy state immunity to the disease of nationalism was ticking. As I have already said, the mine was the right of secession from the Soviet Union.

In the mid-1980s, the increasing socioeconomic problems and the apparent crisis of the planned economy aggravated the ethnic issue, which essentially was not based on any expectations or unfulfilled dreams of the Soviet peoples but primarily the growing appetites of the local elites.

However, instead of analysing the situation, taking appropriate measures, first of all in the economy, and gradually transforming the political system and government in a well-considered and balanced manner, the Communist Party leadership only engaged in open doubletalk about the revival of the Leninist principle of national self-determination.

Moreover, in the course of power struggle within the Communist Party itself, each of the opposing sides, in a bid to expand its support base, started to thoughtlessly incite and encourage nationalist sentiments, manipulating them and promising their potential supporters whatever they wished. Against the backdrop of the superficial and populist rhetoric about democracy and a bright future based either on a market or a planned economy, but amid a true impoverishment of people and widespread shortages, no one among the powers that be was thinking about the inevitable tragic consequences for the country.

Next, they entirely embarked on the track beaten at the inception of the USSR and pandering to the ambitions of the nationalist elites nurtured within their own party ranks. But in so doing, they forgot that the CPSU no longer had – thank God – the tools for retaining power and the country itself, tools such as state terror and a Stalinist-type dictatorship, and that the notorious guiding role of the party was disappearing without a trace, like a morning mist, right before their eyes.

And then, the September 1989 plenary session of the CPSU Central Committee approved a truly fatal document, the so-called ethnic policy of the party in modern conditions, the CPSU platform. It included the following provisions, I quote: “The republics of the USSR shall possess all the rights appropriate to their status as sovereign socialist states.”

The next point: “The supreme representative bodies of power of the USSR republics can challenge and suspend the operation of the USSR Government’s resolutions and directives in their territory.”

And finally: “Each republic of the USSR shall have citizenship of its own, which shall apply to all of its residents.”

Wasn’t it clear what these formulas and decisions would lead to?

Now is not the time or place to go into matters pertaining to state or constitutional law, or define the concept of citizenship. But one may wonder: why was it necessary to rock the country even more in that already complicated situation? The facts remain.

Even two years before the collapse of the USSR, its fate was actually predetermined. It is now that radicals and nationalists, including and primarily those in Ukraine, are taking credit for having gained independence. As we can see, this is absolutely wrong. The disintegration of our united country was brought about by the historic, strategic mistakes on the part of the Bolshevik leaders and the CPSU leadership, mistakes committed at different times in state-building and in economic and ethnic policies. The collapse of the historical Russia known as the USSR is on their conscience.

Despite all these injustices, lies and outright pillage of Russia, it was our people who accepted the new geopolitical reality that took shape after the dissolution of the USSR, and recognised the new independent states. Not only did Russia recognise these countries, but helped its CIS partners, even though it faced a very dire situation itself. This included our Ukrainian colleagues, who turned to us for financial support many times from the very moment they declared independence. Our country provided this assistance while respecting Ukraine’s dignity and sovereignty.

According to expert assessments, confirmed by a simple calculation of our energy prices, the subsidised loans Russia provided to Ukraine along with economic and trade preferences, the overall benefit for the Ukrainian budget in the period from 1991 to 2013 amounted to $250 billion.

However, there was more to it than that. By the end of 1991, the USSR owed some $100 billion to other countries and international funds. Initially, there was this idea that all former Soviet republics will pay back these loans together, in the spirit of solidarity and proportionally to their economic potential. However, Russia undertook to pay back all Soviet debts and delivered on this promise by completing this process in 2017.

In exchange for that, the newly independent states had to hand over to Russia part of the Soviet foreign assets. An agreement to this effect was reached with Ukraine in December 1994. However, Kiev failed to ratify these agreements and later simply refused to honour them by making demands for a share of the Diamond Treasury, gold reserves, as well as former USSR property and other assets abroad.

Nevertheless, despite all these challenges, Russia always worked with Ukraine in an open and honest manner and, as I have already said, with respect for its interests. We developed our ties in multiple fields. Thus, in 2011, bilateral trade exceeded $50 billion. Let me note that in 2019, that is before the pandemic, Ukraine’s trade with all EU countries combined was below this indicator.

At the same time, it was striking how the Ukrainian authorities always preferred dealing with Russia in a way that ensured that they enjoy all the rights and privileges while remaining free from any obligations.

The officials in Kiev replaced partnership with a parasitic attitude acting at times in an extremely brash manner. Suffice it to recall the continuous blackmail on energy transits and the fact that they literally stole gas.

I can add that Kiev tried to use dialogue with Russia as a bargaining chip in its relations with the West, using the threat of closer ties with Russia for blackmailing the West to secure preferences by claiming that otherwise Russia would have a bigger influence in Ukraine.

At the same time, the Ukrainian authorities – I would like to emphasise this – began by building their statehood on the negation of everything that united us, trying to distort the mentality and historical memory of millions of people, of entire generations living in Ukraine. It is not surprising that Ukrainian society was faced with the rise of far-right nationalism, which rapidly developed into aggressive Russophobia and neo-Nazism. This resulted in the participation of Ukrainian nationalists and neo-Nazis in the terrorist groups in the North Caucasus and the increasingly loud territorial claims to Russia.

A role in this was played by external forces, which used a ramified network of NGOs and special services to nurture their clients in Ukraine and to bring their representatives to the seats of authority.

It should be noted that Ukraine actually never had stable traditions of real statehood. And, therefore, in 1991 it opted for mindlessly emulating foreign models, which have no relation to history or Ukrainian realities. Political government institutions were readjusted many times to the rapidly growing clans and their self-serving interests, which had nothing to do with the interests of the Ukrainian people.

Essentially, the so-called pro-Western civilisational choice made by the oligarchic Ukrainian authorities was not and is not aimed at creating better conditions in the interests of people’s well-being but at keeping the billions of dollars that the oligarchs have stolen from the Ukrainians and are holding in their accounts in Western banks, while reverently accommodating the geopolitical rivals of Russia.

Some industrial and financial groups and the parties and politicians on their payroll relied on the nationalists and radicals from the very beginning. Others claimed to be in favour of good relations with Russia and cultural and language diversity, coming to power with the help of their citizens who sincerely supported their declared aspirations, including the millions of people in the south-eastern regions. But after getting the positions they coveted, these people immediately betrayed their voters, going back on their election promises and instead steering a policy prompted by the radicals and sometimes even persecuting their former allies – the public organisations that supported bilingualism and cooperation with Russia. These people took advantage of the fact that their voters were mostly law-abiding citizens with moderate views who trusted the authorities, and that, unlike the radicals, they would not act aggressively or make use of illegal instruments.

Meanwhile, the radicals became increasingly brazen in their actions and made more demands every year. They found it easy to force their will on the weak authorities, which were infected with the virus of nationalism and corruption as well and which artfully replaced the real cultural, economic and social interests of the people and Ukraine’s true sovereignty with various ethnic speculations and formal ethnic attributes.

A stable statehood has never developed in Ukraine; its electoral and other political procedures just serve as a cover, a screen for the redistribution of power and property between various oligarchic clans.

Corruption, which is certainly a challenge and a problem for many countries, including Russia, has gone beyond the usual scope in Ukraine. It has literally permeated and corroded Ukrainian statehood, the entire system, and all branches of power.

Radical nationalists took advantage of the justified public discontent and saddled the Maidan protest, escalating it to a coup d’état in 2014. They also had direct assistance from foreign states. According to reports, the US Embassy provided $1 million a day to support the so-called protest camp on Independence Square in Kiev. In addition, large amounts were impudently transferred directly to the opposition leaders’ bank accounts, tens of millions of dollars. But the people who actually suffered, the families of those who died in the clashes provoked in the streets and squares of Kiev and other cities, how much did they get in the end? Better not ask.

The nationalists who have seized power have unleashed a persecution, a real terror campaign against those who opposed their anti-constitutional actions. Politicians, journalists, and public activists were harassed and publicly humiliated. A wave of violence swept Ukrainian cities, including a series of high-profile and unpunished murders. One shudders at the memories of the terrible tragedy in Odessa, where peaceful protesters were brutally murdered, burned alive in the House of Trade Unions. The criminals who committed that atrocity have never been punished, and no one is even looking for them. But we know their names and we will do everything to punish them, find them and bring them to justice.

Maidan did not bring Ukraine any closer to democracy and progress. Having accomplished a coup d’état, the nationalists and those political forces that supported them eventually led Ukraine into an impasse, pushed the country into the abyss of civil war. Eight years later, the country is split. Ukraine is struggling with an acute socioeconomic crisis.

According to international organisations, in 2019, almost 6 million Ukrainians – I emphasise – about 15 percent, not of the wokrforce, but of the entire population of that country, had to go abroad to find work. Most of them do odd jobs. The following fact is also revealing: since 2020, over 60,000 doctors and other health workers have left the country amid the pandemic.